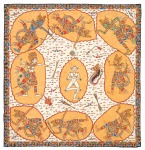

How to convert old, much-cherished, Javanese and Balinese batik sarongs into something useful in this year of pandemia? Memories of favorite fabrics from the past re-purposed into well-made masks? Why not?

Dana Cooper, a Bermuda-based designer, suggested I call Pauline Lock at In Style USA in NYC’s garment district. Pauline said, “Let’s see what we can do….”

Most of the sarongs had a single tear where they’d received the most wear.

Plenty of material–including some from other non-Indonesian, non-batik fabric–to make enough masks for Christmas presents to extended family.

One of those old pieces was an almost 50-year-old George McGovern t-shirt that I’d embroidered while sailing from Hawai’i to Tahiti in 1971.

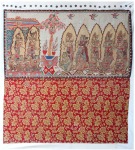

The three pieces on the left above are first layers of non-batik textile. The second piece from the right is the middle layer of DuPont Silvadur antimicrobial fabric, and the interior layer of fine soft cotton is on the right.

InDesign’s people measured and cut all the fabric and manufactured 58 masks over a couple of working days…

… and delivered them in time for close-to-Christmas mailing,….

and every one recalls memories from the past four decades.